Introduction

Time series provide the opportunity to forecast future values. Based on previous values, time series can be used to forecast trends in economics, weather, and capacity planning, to name a few. The specific properties of time-series data mean that specialized statistical methods are usually required.

In this tutorial, we will aim to produce reliable forecasts of time series. We will begin by introducing and discussing the concepts of autocorrelation, stationarity, and seasonality, and proceed to apply one of the most commonly used method for time-series forecasting, known as ARIMA.

One of the methods available in Python to model and predict future points of a time series is known as SARIMAX, which stands for Seasonal AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Averages with eXogenous regressors. Here, we will primarily focus on the ARIMA component, which is used to fit time-series data to better understand and forecast future points in the time series.

Prerequisites

This guide will cover how to do time-series analysis on either a local desktop or a remote server. Working with large datasets can be memory intensive, so in either case, the computer will need at least 2GB of memory to perform some of the calculations in this guide.

To make the most of this tutorial, some familiarity with time series and statistics can be helpful.

For this tutorial, we’ll be using Jupyter Notebook to work with the data. If you do not have it already, you should follow our tutorial to install and set up Jupyter Notebook for Python 3.

Step 1 — Installing Packages

To set up our environment for time-series forecasting, let’s first move into our local programming environment or server-based programming environment:

From here, let’s create a new directory for our project. We will call it ARIMA and then move into the directory. If you call the project a different name, be sure to substitute your name for ARIMA throughout the guide

This tutorial will require the warnings, itertools, pandas, numpy, matplotlib and statsmodels libraries. The warnings and itertools libraries come included with the standard Python library set so you shouldn’t need to install them.

Like with other Python packages, we can install these requirements with pip.

We can now install pandas, statsmodels, and the data plotting package matplotlib. Their dependencies will also be installed:

- pip install pandas numpy statsmodels matplotlib

At this point, we’re now set up to start working with the installed packages.

Step 2 — Importing Packages and Loading Data

To begin working with our data, we will start up Jupyter Notebook:

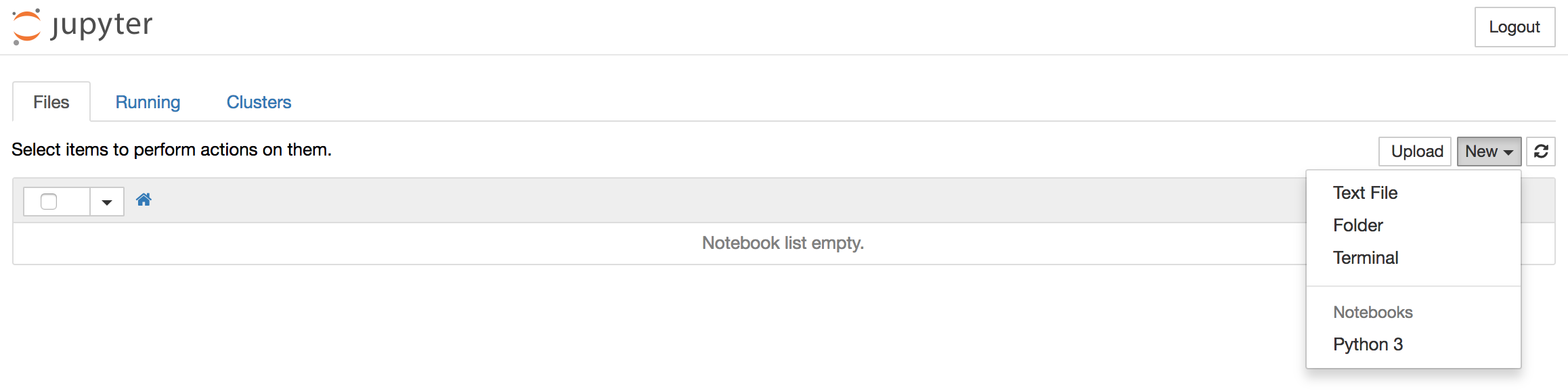

To create a new notebook file, select New > Python 3 from the top right pull-down menu:

This will open a notebook.

As is best practice, start by importing the libraries you will need at the top of your notebook:

import warnings

import itertools

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import statsmodels.api as sm

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.style.use('fivethirtyeight')

We have also defined a matplotlib style of fivethirtyeight for our plots.

We’ll be working with a dataset called “Atmospheric CO2 from Continuous Air Samples at Mauna Loa Observatory, Hawaii, U.S.A.,” which collected CO2 samples from March 1958 to December 2001. We can bring in this data as follows:

data = sm.datasets.co2.load_pandas()

y = data.data

Let’s preprocess our data a little bit before moving forward. Weekly data can be tricky to work with since it’s a briefer amount of time, so let’s use monthly averages instead. We’ll make the conversion with the resample function. For simplicity, we can also use the fillna() function to ensure that we have no missing values in our time series.

y = y['co2'].resample('MS').mean()

y = y.fillna(y.bfill())

print(y)

Output

co2

1958-03-01 316.100000

1958-04-01 317.200000

1958-05-01 317.433333

...

2001-11-01 369.375000

2001-12-01 371.020000

Let’s explore this time series e as a data visualization:

y.plot(figsize=(15, 6))

plt.show()

Some distinguishable patterns appear when we plot the data. The time series has an obvious seasonality pattern, as well as an overall increasing trend.

To learn more about time series pre-processing, please refer to “A Guide to Time Series Visualization with Python 3,” where the steps above are described in much more detail.

Now that we’ve converted and explored our data, let’s move on to time series forecasting with ARIMA.

Step 3 — The ARIMA Time Series Model

One of the most common methods used in time series forecasting is known as the ARIMA model, which stands for AutoregRessive Integrated Moving Average. ARIMA is a model that can be fitted to time series data in order to better understand or predict future points in the series.

There are three distinct integers (p, d, q) that are used to parametrize ARIMA models. Because of that, ARIMA models are denoted with the notation ARIMA(p, d, q). Together these three parameters account for seasonality, trend, and noise in datasets:

p is the auto-regressive part of the model. It allows us to incorporate the effect of past values into our model. Intuitively, this would be similar to stating that it is likely to be warm tomorrow if it has been warm the past 3 days.d is the integrated part of the model. This includes terms in the model that incorporate the amount of differencing (i.e. the number of past time points to subtract from the current value) to apply to the time series. Intuitively, this would be similar to stating that it is likely to be same temperature tomorrow if the difference in temperature in the last three days has been very small.q is the moving average part of the model. This allows us to set the error of our model as a linear combination of the error values observed at previous time points in the past.

When dealing with seasonal effects, we make use of the seasonal ARIMA, which is denoted as ARIMA(p,d,q)(P,D,Q)s. Here, (p, d, q) are the non-seasonal parameters described above, while (P, D, Q) follow the same definition but are applied to the seasonal component of the time series. The term s is the periodicity of the time series (4 for quarterly periods, 12 for yearly periods, etc.).

The seasonal ARIMA method can appear daunting because of the multiple tuning parameters involved. In the next section, we will describe how to automate the process of identifying the optimal set of parameters for the seasonal ARIMA time series model.

Step 4 — Parameter Selection for the ARIMA Time Series Model

When looking to fit time series data with a seasonal ARIMA model, our first goal is to find the values of ARIMA(p,d,q)(P,D,Q)s that optimize a metric of interest. There are many guidelines and best practices to achieve this goal, yet the correct parametrization of ARIMA models can be a painstaking manual process that requires domain expertise and time. Other statistical programming languages such as R provide automated ways to solve this issue, but those have yet to be ported over to Python. In this section, we will resolve this issue by writing Python code to programmatically select the optimal parameter values for our ARIMA(p,d,q)(P,D,Q)s time series model.

We will use a “grid search” to iteratively explore different combinations of parameters. For each combination of parameters, we fit a new seasonal ARIMA model with the SARIMAX() function from the statsmodels module and assess its overall quality. Once we have explored the entire landscape of parameters, our optimal set of parameters will be the one that yields the best performance for our criteria of interest. Let’s begin by generating the various combination of parameters that we wish to assess:

p = d = q = range(0, 2)

pdq = list(itertools.product(p, d, q))

seasonal_pdq = [(x[0], x[1], x[2], 12) for x in list(itertools.product(p, d, q))]

print('Examples of parameter combinations for Seasonal ARIMA...')

print('SARIMAX: {} x {}'.format(pdq[1], seasonal_pdq[1]))

print('SARIMAX: {} x {}'.format(pdq[1], seasonal_pdq[2]))

print('SARIMAX: {} x {}'.format(pdq[2], seasonal_pdq[3]))

print('SARIMAX: {} x {}'.format(pdq[2], seasonal_pdq[4]))

Output

Examples of parameter combinations for Seasonal ARIMA...

SARIMAX: (0, 0, 1) x (0, 0, 1, 12)

SARIMAX: (0, 0, 1) x (0, 1, 0, 12)

SARIMAX: (0, 1, 0) x (0, 1, 1, 12)

SARIMAX: (0, 1, 0) x (1, 0, 0, 12)

We can now use the triplets of parameters defined above to automate the process of training and evaluating ARIMA models on different combinations. In Statistics and Machine Learning, this process is known as grid search (or hyperparameter optimization) for model selection.

When evaluating and comparing statistical models fitted with different parameters, each can be ranked against one another based on how well it fits the data or its ability to accurately predict future data points. We will use the AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) value, which is conveniently returned with ARIMA models fitted using statsmodels. The AIC measures how well a model fits the data while taking into account the overall complexity of the model. A model that fits the data very well while using lots of features will be assigned a larger AIC score than a model that uses fewer features to achieve the same goodness-of-fit. Therefore, we are interested in finding the model that yields the lowest AIC value.

The code chunk below iterates through combinations of parameters and uses the SARIMAX function from statsmodels to fit the corresponding Seasonal ARIMA model. Here, the order argument specifies the (p, d, q) parameters, while the seasonal_order argument specifies the (P, D, Q, S) seasonal component of the Seasonal ARIMA model. After fitting each SARIMAX()model, the code prints out its respective AICscore.

warnings.filterwarnings("ignore")

for param in pdq:

for param_seasonal in seasonal_pdq:

try:

mod = sm.tsa.statespace.SARIMAX(y,

order=param,

seasonal_order=param_seasonal,

enforce_stationarity=False,

enforce_invertibility=False)

results = mod.fit()

print('ARIMA{}x{}12 - AIC:{}'.format(param, param_seasonal, results.aic))

except:

continue

Because some parameter combinations may lead to numerical misspecifications, we explicitly disabled warning messages in order to avoid an overload of warning messages. These misspecifications can also lead to errors and throw an exception, so we make sure to catch these exceptions and ignore the parameter combinations that cause these issues.

The code above should yield the following results, this may take some time:

Output

SARIMAX(0, 0, 0)x(0, 0, 1, 12) - AIC:6787.3436240402125

SARIMAX(0, 0, 0)x(0, 1, 1, 12) - AIC:1596.711172764114

SARIMAX(0, 0, 0)x(1, 0, 0, 12) - AIC:1058.9388921320026

SARIMAX(0, 0, 0)x(1, 0, 1, 12) - AIC:1056.2878315690562

SARIMAX(0, 0, 0)x(1, 1, 0, 12) - AIC:1361.6578978064144

SARIMAX(0, 0, 0)x(1, 1, 1, 12) - AIC:1044.7647912940095

...

...

...

SARIMAX(1, 1, 1)x(1, 0, 0, 12) - AIC:576.8647112294245

SARIMAX(1, 1, 1)x(1, 0, 1, 12) - AIC:327.9049123596742

SARIMAX(1, 1, 1)x(1, 1, 0, 12) - AIC:444.12436865161305

SARIMAX(1, 1, 1)x(1, 1, 1, 12) - AIC:277.7801413828764

The output of our code suggests that SARIMAX(1, 1, 1)x(1, 1, 1, 12) yields the lowest AIC value of 277.78. We should therefore consider this to be optimal option out of all the models we have considered.

Step 5 — Fitting an ARIMA Time Series Model

Using grid search, we have identified the set of parameters that produces the best fitting model to our time series data. We can proceed to analyze this particular model in more depth.

We’ll start by plugging the optimal parameter values into a new SARIMAX model:

mod = sm.tsa.statespace.SARIMAX(y,

order=(1, 1, 1),

seasonal_order=(1, 1, 1, 12),

enforce_stationarity=False,

enforce_invertibility=False)

results = mod.fit()

print(results.summary().tables[1])

Output

==============================================================================

coef std err z P>|z| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

ar.L1 0.3182 0.092 3.443 0.001 0.137 0.499

ma.L1 -0.6255 0.077 -8.165 0.000 -0.776 -0.475

ar.S.L12 0.0010 0.001 1.732 0.083 -0.000 0.002

ma.S.L12 -0.8769 0.026 -33.811 0.000 -0.928 -0.826

sigma2 0.0972 0.004 22.634 0.000 0.089 0.106

==============================================================================

The summary attribute that results from the output of SARIMAX returns a significant amount of information, but we’ll focus our attention on the table of coefficients. The coef column shows the weight (i.e. importance) of each feature and how each one impacts the time series. The P>|z| column informs us of the significance of each feature weight. Here, each weight has a p-value lower or close to 0.05, so it is reasonable to retain all of them in our model.

When fitting seasonal ARIMA models (and any other models for that matter), it is important to run model diagnostics to ensure that none of the assumptions made by the model have been violated. The plot_diagnostics object allows us to quickly generate model diagnostics and investigate for any unusual behavior.

results.plot_diagnostics(figsize=(15, 12))

plt.show()

Our primary concern is to ensure that the residuals of our model are uncorrelated and normally distributed with zero-mean. If the seasonal ARIMA model does not satisfy these properties, it is a good indication that it can be further improved.

In this case, our model diagnostics suggests that the model residuals are normally distributed based on the following:

- In the top right plot, we see that the red

KDE line follows closely with the N(0,1) line (where N(0,1)) is the standard notation for a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation of 1). This is a good indication that the residuals are normally distributed.

- The qq-plot on the bottom left shows that the ordered distribution of residuals (blue dots) follows the linear trend of the samples taken from a standard normal distribution with

N(0, 1). Again, this is a strong indication that the residuals are normally distributed.

- The residuals over time (top left plot) don’t display any obvious seasonality and appear to be white noise. This is confirmed by the autocorrelation (i.e. correlogram) plot on the bottom right, which shows that the time series residuals have low correlation with lagged versions of itself.

Those observations lead us to conclude that our model produces a satisfactory fit that could help us understand our time series data and forecast future values.

Although we have a satisfactory fit, some parameters of our seasonal ARIMA model could be changed to improve our model fit. For example, our grid search only considered a restricted set of parameter combinations, so we may find better models if we widened the grid search.

Step 6 — Validating Forecasts

We have obtained a model for our time series that can now be used to produce forecasts. We start by comparing predicted values to real values of the time series, which will help us understand the accuracy of our forecasts. The get_prediction() and conf_int() attributes allow us to obtain the values and associated confidence intervals for forecasts of the time series.

pred = results.get_prediction(start=pd.to_datetime('1998-01-01'), dynamic=False)

pred_ci = pred.conf_int()

The code above requires the forecasts to start at January 1998.

The dynamic=False argument ensures that we produce one-step ahead forecasts, meaning that forecasts at each point are generated using the full history up to that point.

We can plot the real and forecasted values of the CO2 time series to assess how well we did. Notice how we zoomed in on the end of the time series by slicing the date index.

ax = y['1990':].plot(label='observed')

pred.predicted_mean.plot(ax=ax, label='One-step ahead Forecast', alpha=.7)

ax.fill_between(pred_ci.index,

pred_ci.iloc[:, 0],

pred_ci.iloc[:, 1], color='k', alpha=.2)

ax.set_xlabel('Date')

ax.set_ylabel('CO2 Levels')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Overall, our forecasts align with the true values very well, showing an overall increase trend.

It is also useful to quantify the accuracy of our forecasts. We will use the MSE (Mean Squared Error), which summarizes the average error of our forecasts. For each predicted value, we compute its distance to the true value and square the result. The results need to be squared so that positive/negative differences do not cancel each other out when we compute the overall mean.

y_forecasted = pred.predicted_mean

y_truth = y['1998-01-01':]

mse = ((y_forecasted - y_truth) ** 2).mean()

print('The Mean Squared Error of our forecasts is {}'.format(round(mse, 2)))

Output

The Mean Squared Error of our forecasts is 0.07

The MSE of our one-step ahead forecasts yields a value of 0.07, which is very low as it is close to 0. An MSE of 0 would that the estimator is predicting observations of the parameter with perfect accuracy, which would be an ideal scenario but it not typically possible.

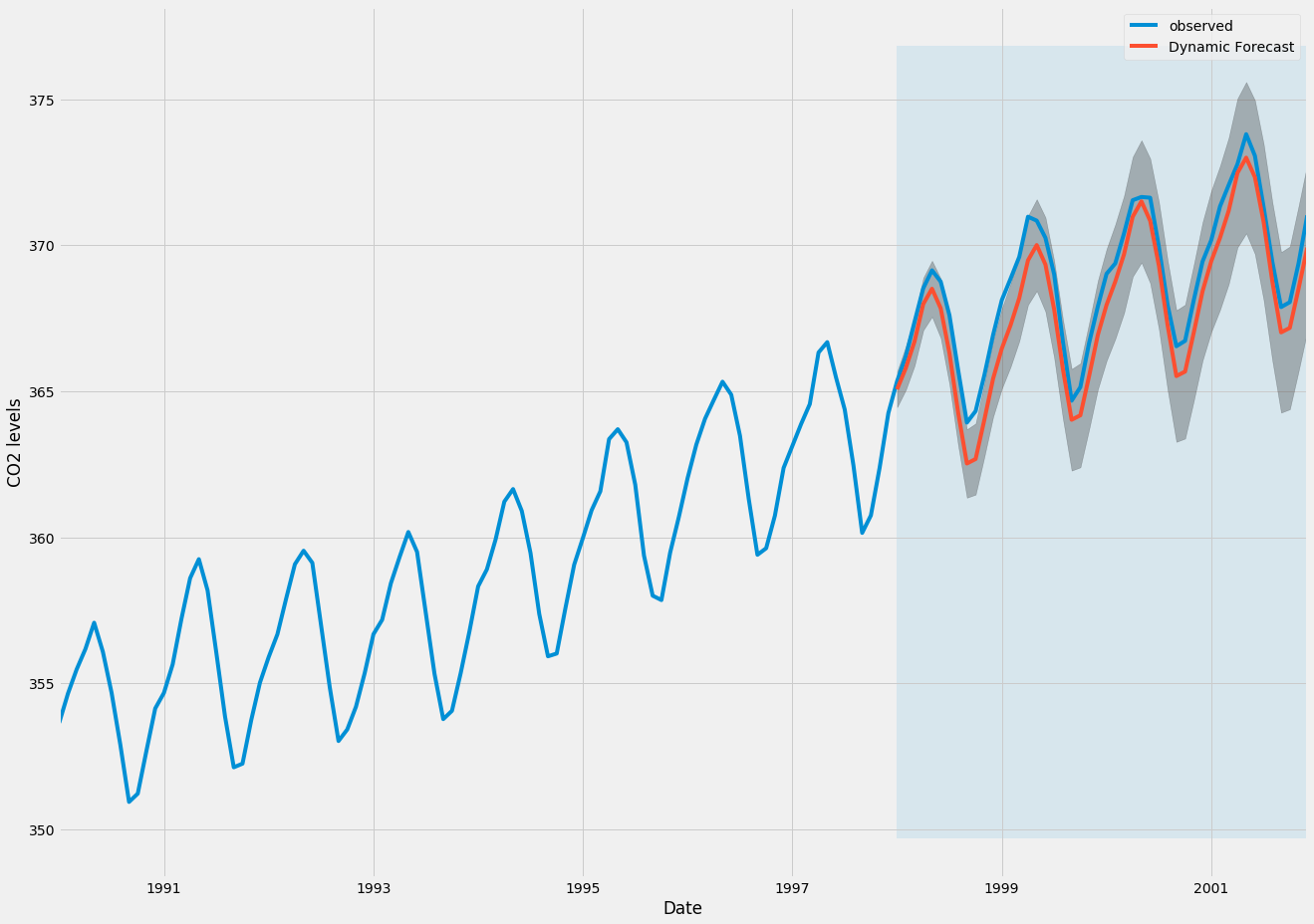

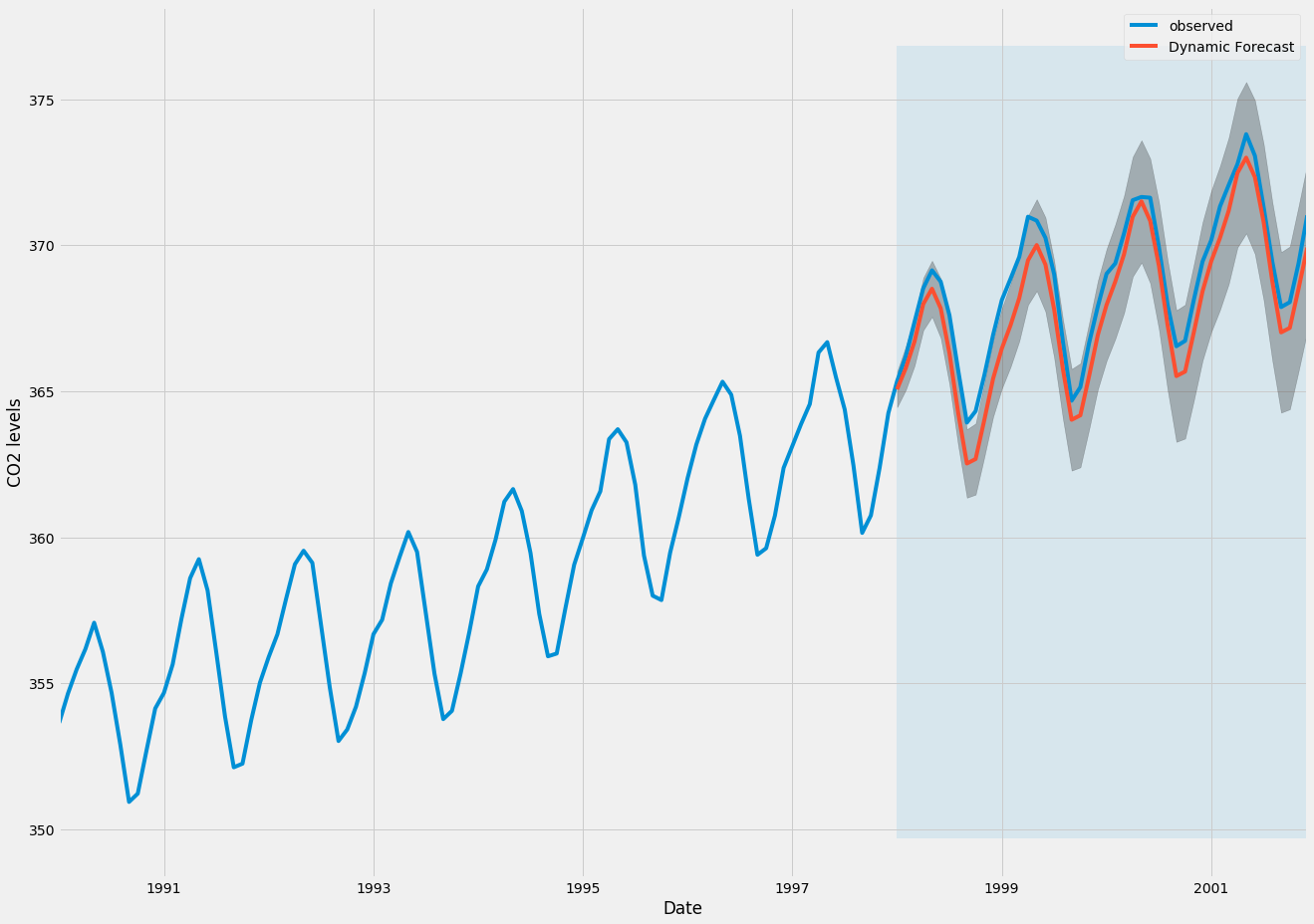

However, a better representation of our true predictive power can be obtained using dynamic forecasts. In this case, we only use information from the time series up to a certain point, and after that, forecasts are generated using values from previous forecasted time points.

In the code chunk below, we specify to start computing the dynamic forecasts and confidence intervals from January 1998 onwards.

pred_dynamic = results.get_prediction(start=pd.to_datetime('1998-01-01'), dynamic=True, full_results=True)

pred_dynamic_ci = pred_dynamic.conf_int()

Plotting the observed and forecasted values of the time series, we see that the overall forecasts are accurate even when using dynamic forecasts. All forecasted values (red line) match pretty closely to the ground truth (blue line), and are well within the confidence intervals of our forecast.

ax = y['1990':].plot(label='observed', figsize=(20, 15))

pred_dynamic.predicted_mean.plot(label='Dynamic Forecast', ax=ax)

ax.fill_between(pred_dynamic_ci.index,

pred_dynamic_ci.iloc[:, 0],

pred_dynamic_ci.iloc[:, 1], color='k', alpha=.25)

ax.fill_betweenx(ax.get_ylim(), pd.to_datetime('1998-01-01'), y.index[-1],

alpha=.1, zorder=-1)

ax.set_xlabel('Date')

ax.set_ylabel('CO2 Levels')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Once again, we quantify the predictive performance of our forecasts by computing the MSE:

y_forecasted = pred_dynamic.predicted_mean

y_truth = y['1998-01-01':]

mse = ((y_forecasted - y_truth) ** 2).mean()

print('The Mean Squared Error of our forecasts is {}'.format(round(mse, 2)))

Output

The Mean Squared Error of our forecasts is 1.01

The predicted values obtained from the dynamic forecasts yield an MSE of 1.01. This is slightly higher than the one-step ahead, which is to be expected given that we are relying on less historical data from the time series.

Both the one-step ahead and dynamic forecasts confirm that this time series model is valid. However, much of the interest around time series forecasting is the ability to forecast future values way ahead in time.

Step 7 — Producing and Visualizing Forecasts

In the final step of this tutorial, we describe how to leverage our seasonal ARIMA time series model to forecast future values. The get_forecast() attribute of our time series object can compute forecasted values for a specified number of steps ahead.

pred_uc = results.get_forecast(steps=500)

pred_ci = pred_uc.conf_int()

We can use the output of this code to plot the time series and forecasts of its future values.

ax = y.plot(label='observed', figsize=(20, 15))

pred_uc.predicted_mean.plot(ax=ax, label='Forecast')

ax.fill_between(pred_ci.index,

pred_ci.iloc[:, 0],

pred_ci.iloc[:, 1], color='k', alpha=.25)

ax.set_xlabel('Date')

ax.set_ylabel('CO2 Levels')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Both the forecasts and associated confidence interval that we have generated can now be used to further understand the time series and foresee what to expect. Our forecasts show that the time series is expected to continue increasing at a steady pace.

As we forecast further out into the future, it is natural for us to become less confident in our values. This is reflected by the confidence intervals generated by our model, which grow larger as we move further out into the future.

Conclusion

In this tutorial, we described how to implement a seasonal ARIMA model in Python. We made extensive use of the pandas and statsmodels libraries and showed how to run model diagnostics, as well as how to produce forecasts of the CO2 time series.

Here are a few other things you could try:

- Change the start date of your dynamic forecasts to see how this affects the overall quality of your forecasts.

- Try more combinations of parameters to see if you can improve the goodness-of-fit of your model.

- Select a different metric to select the best model. For example, we used the

AIC measure to find the best model, but you could seek to optimize the out-of-sample mean square error instead.

For more practice, you could also try to load another time series dataset to produce your own forecasts.

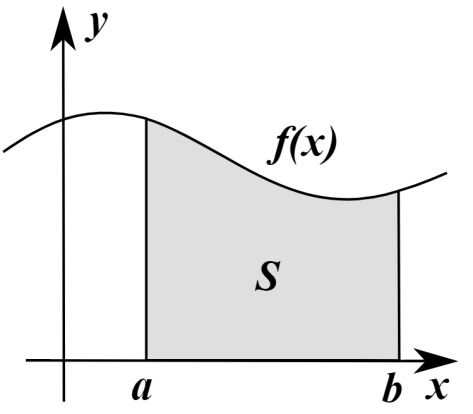

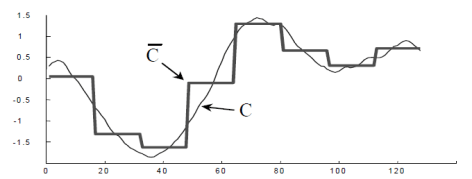

和余弦函数

,只是平移了

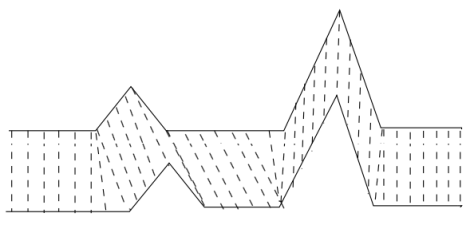

个长度而已。本文将会介绍一些基于形状的时间序列的距离算法,并且介绍如何在给定时间序列的情况下,在时间序列数据库中寻找相似的时间序列。

和

。首先我们可以建立一个

的矩阵,

位置的元素是

,这里的 dist 可以使用

范数。其次,我们想找到一条路径,使得这个矩阵的累积距离最小,而这条路则是两条时间序列之间的最佳匹配。在这里,我们可以假设这条路径是

,其中

的每个元素表示时间序列 Q 中的第 i 个元素和时间序列 C 中的第 j 个元素之间的距离. i.e.

。

.

,有

最终的取值

就是我们需要的解,也就是两条时间序列的 DTW 距离。按照上面的算法,DTW 算法的时间复杂度是

。特别地,

时,则

表示最后的距离;

时,则

表示最后的距离。

时,则

表示最后的距离。

,则

与

的话,i 与 j 需要满足

,这里的 w 表示窗口长度。因此算法的描述如下:

取值范围是:对每一个

,需要

满足

。

和一个时间序列的数据库

。通过某种相似度或者距离计算方法,计算出给定的时间序列

与时间序列数据库中

中最相似的时间序列。

和一个时间序列的数据库

,以及正整数

。从数据库

中寻找与给定的时间序列

最相似的

条时间序列。

.

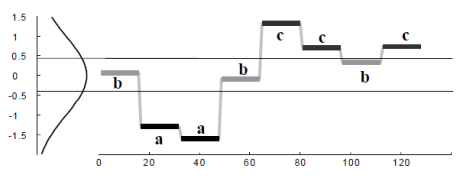

。于是就有学者研究是否存在 DTW 距离的下界表示,也就是说找到一个合适的下界,Lower Bound of DTW。每次判断 Lower Bound of DTW 是否小于当前的最小距离,如果下界高于最小距离,就不需要进行 DTW 的计算;否则开始计算 DTW 的值。如果下界的计算速度足够快,并且下界足够精准的话,可以大量的压缩搜索的时间。于是,Keogh 提出了下界的计算方法。

,给定一个窗口的取值 r,得到

,

。

,有不等式

成立。

.

9 Comments